The commander of the submarine Sh-303 "Pike" tells...

From the Author: in No. 5 (1960) of the magazine “Soviet Sailor” I talked about how submarines under the command of Y. Afanasyev, I. Vishnevsky, E. Osipov, L. Lisin in the summer of 1942 crossed the minefields of the Hogland and Porkkala-Udd anti-submarine lines of the Finnish bay. After the successful combat operations of the submariners, the Nazis further strengthened their anti-submarine lines, placing eight and a half thousand mines by the end of April 1943. a noise direction-finding station and network booms across the entire Gulf of Finland.

The command assigned the submarine Shch-303, which I commanded, to carry out reconnaissance of the borders. I would like to talk about this military campaign.

* * *

At the beginning of May, when the white nights were already approaching in the Baltics, Shch-303 went out to carry out a difficult combat mission.

They decided to force the Gogland line through the Narva Bay. Magnetic and anti-boat mines posed a great danger here. We were especially concerned about the latter. The Nazis tied such mines with wire and sank them, and they could be wound around the propeller.

When approaching the minefield, the hydroacoustic recorded several deep-seated explosions in the direction of Narva Bay. This means that there were anti-submarine defense ships there. And almost at the same instant, the excited voice of Lieutenant Butyrsky was heard in the speaking tube.

— There’s a minrepa grinding on your nose to the right!

Soon everyone heard an ominous sound. It was as if the Minrep was caught on something or was pulled to the hull of the boat by a magnet.

“Right steering wheel,” I gave the command.

The Ministry of Repair, and with it the mine, came off the boat’s hull.

“The Old Lady,” as they called it at formation Shch-303, slowly moved almost along the very bottom of the bay, every now and then colliding with mines. At times it seemed to us that it was impossible to get through this minefield. But still we stubbornly moved forward.

It's time to change the ship's course. Doing this in a minefield is very dangerous, since when turning, you can wind the minerep around the screw. We had barely set off on a new course when they reported from the first compartment that dull blows against the hull were heard from the starboard side. I ordered the steering wheel to be slowly shifted to the right. However, the strikes continued to move towards the stern. It seemed as if someone was hitting the side of the ship with a hammer. We understood: the submarine was not touching the mine, but the mine itself. Finally the blows to the body stopped. These terrible moments seemed like an eternity. We had to meet with minreps before, but to feel the pat of a mine on ourselves - this had never happened before.

The next day we went out to the western part of Narva Bay and carried out reconnaissance. The area was clear of mines and anti-submarine ships. The boat floated to the surface. The electricians began charging the battery. We have overcome the Gogland anti-submarine line. But not even an hour had passed before we were attacked by enemy planes. We had to make an urgent dive.

And half an hour later, acoustician Vasiliev reported that anti-submarine defense ships were approaching. At a short distance from us they dropped depth charges.

It became clear that we would not be allowed to charge the battery in this area. I had to change the area. With great difficulty we managed to charge the battery.

Now we had to reconnoiter the most dangerous Naisar - the Porkkala-Udd border. When approaching it, approximately north of the Usmadalek Bank, five anti-submarine defense ships were discovered. They were probably guarding the eastern part of the fence.

Before diving under the nets, it was necessary to reconnoiter the area as best as possible. We walked along it from south to north and watched through the periscope without moving. From Naisar Island to the Porkkalan-Kolboda lighthouse, buoys and barrels stretched in two rows at a distance of approximately 50-70 meters from each other. This means that there are fixed-line networks here. We walk along the networks, again touching the minreps several times.

White nights did not please us this time. It was easier to break through the line in the dark, so that if the boat got stuck in the nets, it would be possible to surface and free itself from them. But there was no choice. We need to decide.

You need to go through the compartments and talk with communists and Komsomol members, find out what they think about the upcoming crossing of the network barrier. In the first compartment, the secretary of the ship's Komsomol organization, commander of the torpedo squad, Alexei Ivanov, was on duty.

— How do the personnel of the compartment feel? - I asked.

“It’s okay, comrade commander, because this is not the first time we’ve encountered mines.” So rest assured for us.

In the torpedo compartment, everything was really in order: the torpedoes were secured on their racks like a storm, the emergency tools were in place, the people looked cheerful. The school of the Komsomol leader is visible. I looked into the sonar room. The acoustician Vasiliev was sitting there. This was his first time taking part in a military campaign.

- Well, is it a little scary, Comrade Vasiliev?

“It’s a little scary without the habit, Comrade Commander.” But whatever is required of me, I will do.

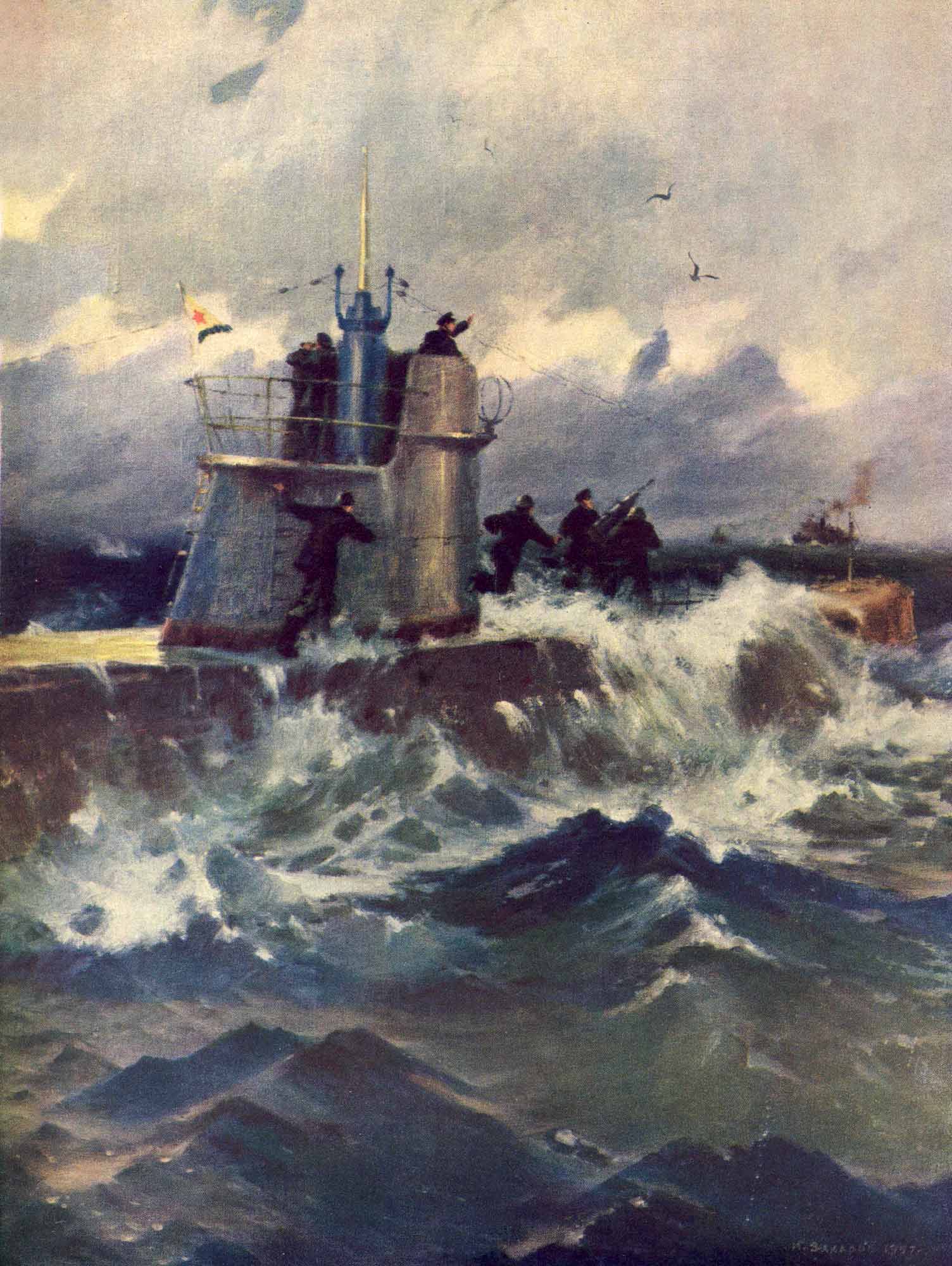

Meeting before the survey of anti-submarine networks. From left to right: engineer-senior lieutenant P. Ilyin, navigator senior lieutenant G. Mogrilov, political officer senior political instructor M. Zeischer, captain of the third rank I. Travkin (photograph of the war years).

With the onset of dusk, we began to break through the network barriers. The ship's course was laid out in such a way as to dive under the nets at maximum depth. The stroke is minimal - only two knots. All personnel are at their combat posts and command posts. We listen to outboard noises. Emergency equipment at the ready.

After about ten minutes, the boatswain reported that the boat was not obeying the horizontal rudders, and the trim was increasing by the bow. And immediately from the first compartment they reported that they could hear the grinding of nets against the side of the ship. “It’s begun!” I thought.

The engines stopped. They turned back. It was difficult to tear myself away from the networks. Having changed course, we once again try to dive under the network barriers. Fifteen minutes later, disaster struck: they were caught in steel nets again. We give a medium stroke back, changing the trim either to the bow or to the stern. A huge explosion shook the boat. Is it really the end? But from the compartments they report: “There is no serious damage.”

I brought the trim up to ten degrees on the bow and ordered the boat to go as far as possible. The submarine trembled and darted back, as if it had escaped from someone’s powerful embrace.

A new attempt to pass under the barrier ended in failure. Network again. This time it's even harder to throw it off. The density of the battery has decreased to 17° and it is impossible to give full speed.

We take water into the aft trim tank and pump it out, jerking it back. But all to no avail. The situation is becoming critical, but not the slightest confusion is visible among the sailors. I order you to bring the trim to 15° on the bow and give the strongest possible jerk with the electric motors back. The boat trembled, moved, as if sliding down a mountain, and began to sink. And a few seconds later the “old woman” lay down on the ground at great depths.

- Let's go! - Everyone at the central post cried out in relief.

There was already a severe lack of oxygen in the compartments. They gave us another portion of oxygen and turned on the regeneration cartridges.

“Comrade commander,” said mechanical engineer Ilyin, “the density of the battery has decreased to 14°, charging is necessary. There is only enough compressed air left for one ascent!

We had to abandon further attempts to break through the network barrier. It was necessary to leave this area to charge the battery and replenish the high pressure air. Literally lying on the ground, we turned on the opposite course from the nets. When approaching the charging area, they again lay down on the ground until dark.

We were under water for three days. I saw that some were already beginning to talk and make involuntary movements. In the living compartment, the commander of the helmsman squad, Ivlechev, sits half asleep, blood flowing from his nose in a trickle. We were under water for three days. I saw that some were already beginning to talk and make involuntary movements. In the living compartment, the commander of the helmsman squad, Ivlechev, sits half asleep, blood flowing from his nose in a trickle.

“Air, air,” he whispers indistinctly.

He ordered the last portion of oxygen from the remaining supply. I looked through the peephole into the fourth compartment. Some motorists are sleeping behind the diesel engines, some are down on their knees. Mechanic Pyotr Ilyin walks around the compartment. This is a young, but demanding and very caring officer, he loves his subordinates, and they answer him in kind. Here Pyotr Ilyin comes up to the sleeping sailor and puts a pillow under his head, straightens the second sailor’s tangled blanket, and covers the seated one with a pea coat.

Finally, night comes. We remember it: it was the night of May 22. Shch-303 surfaced under the periscope. We scanned the horizon. Visibility is poor, but there seems to be nothing suspicious. The acoustician does not hear any extraneous noise. The command sounded:

- Stay in your places, ready to ascend!

The submarine quickly surfaced. I jumped out onto the bridge and suddenly saw nearby a large number of enemy anti-submarine defense boats standing idle. Noticing a boat that appeared on the surface of the sea, the boats rushed towards us.

— Urgent dive!

A moment - and the hatch is battened down, the rapid submersion tank is flooded. Just as unexpectedly as it appeared on the surface of the sea, the boat disappeared into the depths of the sea. It was necessary to urgently go to the maximum depth. This is our only salvation. I ordered the navigator to plot a course so as to lie on the ground in a deep hole. We could not evade while moving due to the low density of the battery.

The boat had barely sunk when the acoustician reported that he could hear the noise of the propellers of many ships at close range. A few minutes later the enemy began depth bombing. We heard explosions very close by, one bomb hit the boat directly, but did not explode, and the rest threw the Shch-303 three meters. The lights in the compartments went out—some of the battery tanks were damaged. The entrance hatches began to leak water. A fire broke out in the fifth compartment of the propulsion power station due to a short circuit. The damaged boat, almost unable to move, was difficult to keep at depth.

It is precisely such hopeless situations that require people to exert the utmost effort. And the sailors immediately began to work - fixing electrical lighting and insulation, damaged batteries. It seemed that in the dim light of emergency lights it was impossible to carry out such work, but mechanical engineer Ilyin, secretary of the party organization, and commander of the electricians department Boris Boytsov, who knew their job well, quickly isolated the damaged batteries, and current appeared in the lighting circuit. Electrician Ivan Gremailo heroically fought the fire in the fifth compartment. Both of his hands were burned, his uniform was on fire, but he managed to put out the fire.

The enemy ships relentlessly continued to bomb us. Meanwhile, a new danger arose: the Shch-303's nose began to trim, and we could not activate the pumps for fear of being discovered. To eliminate trim, part of the crew was moved from the bow to the stern compartments. This helped - the boat leveled out. Soon the sailors eliminated the flow of water through the entrance hatches.

And suddenly, when we hoped that the worst was over, a second terrible explosion shook the boat. It seemed that the steel hull of the ship could not stand it - it would fall apart. We stood there holding our breath. And again there was a crash and a roar. We are tossed from side to side. The lights go out again and again, gritting their teeth and gasping for breath, the submariners repair the damage.

There is only one way out of this situation: go into the minefield. This is the only way we can break away from the ships. I knew that carrying out this decision meant taking a huge risk, but the situation forced me to do it. And as soon as we were drawn into a minefield, the pursuit stopped.

In the center of the mine position, the Shch-303 passed safely, only hitting the mine once. There we explored a square of one mile, making several zigzags underwater, and laid the boat on the ground. By this time, fifty percent of the team could not move, they were suffocating from oxygen starvation.

Having made sure that there were no mines in this square, with the onset of darkness they began to float to the surface without moving. There was not enough high pressure air to blow through the middle tank. I had to take it from the torpedoes. We surfaced in the wheelhouse and began charging the battery.

That night we had the opportunity to stay on the surface for about an hour and a half. On the second night we were attacked by planes, but we avoided diving.

For ten days, every night we surfaced in the center of the surveyed square in a minefield and each time we were bombed by aircraft. During this time, it was possible to increase the density of the battery to 28°. Having left the minefield, we returned to Kronstadt.

During the twenty-day combat campaign, 2,500 bombs were dropped on the submarine. She was subjected to daily harassment. Thanks to the courage, bravery and skill of the personnel, we managed to complete the important task and return to base. The Shch-303 crew was proud that the results of our reconnaissance helped the submariners break into the Baltic and successfully defeat the enemy.

Hero of the Soviet Union

Captain 1st Rank I. Travkin

The section is led by Vice Admiral G. I. Shchedrin

Drawings by E. Seleznevа

Midshipman I. Zakharov. Submariners take the fight, USSR

*** |