Fulcrum - story

The pain was acute, almost physical: the detachment had traveled so many leaden roads, so many difficult victories had been won, people had fraternized so fervently and generously in the military spirit - and now I had to tell everyone: “Go home.”

These hatefully forced conditions of a truce with the Germans lay like a black tourniquet on my throat...

Shchors — he could be the son of some of the partisans—slowly walks around the fighters, says goodbye, and hugs him like a brother. Now in his hand is the rough palm of Zakhar Zapalchishin.

Looking into the young weather-beaten face of the fighter, Shchors extends his second hand to him and for a long time, silently, does not release his palms. Then he says:

“And if it happens, Zakhar, I’ll tell Lenin himself about you.” And about you, and about your dad, and about your brothers.

"If it happens"...

This happened. And soon.

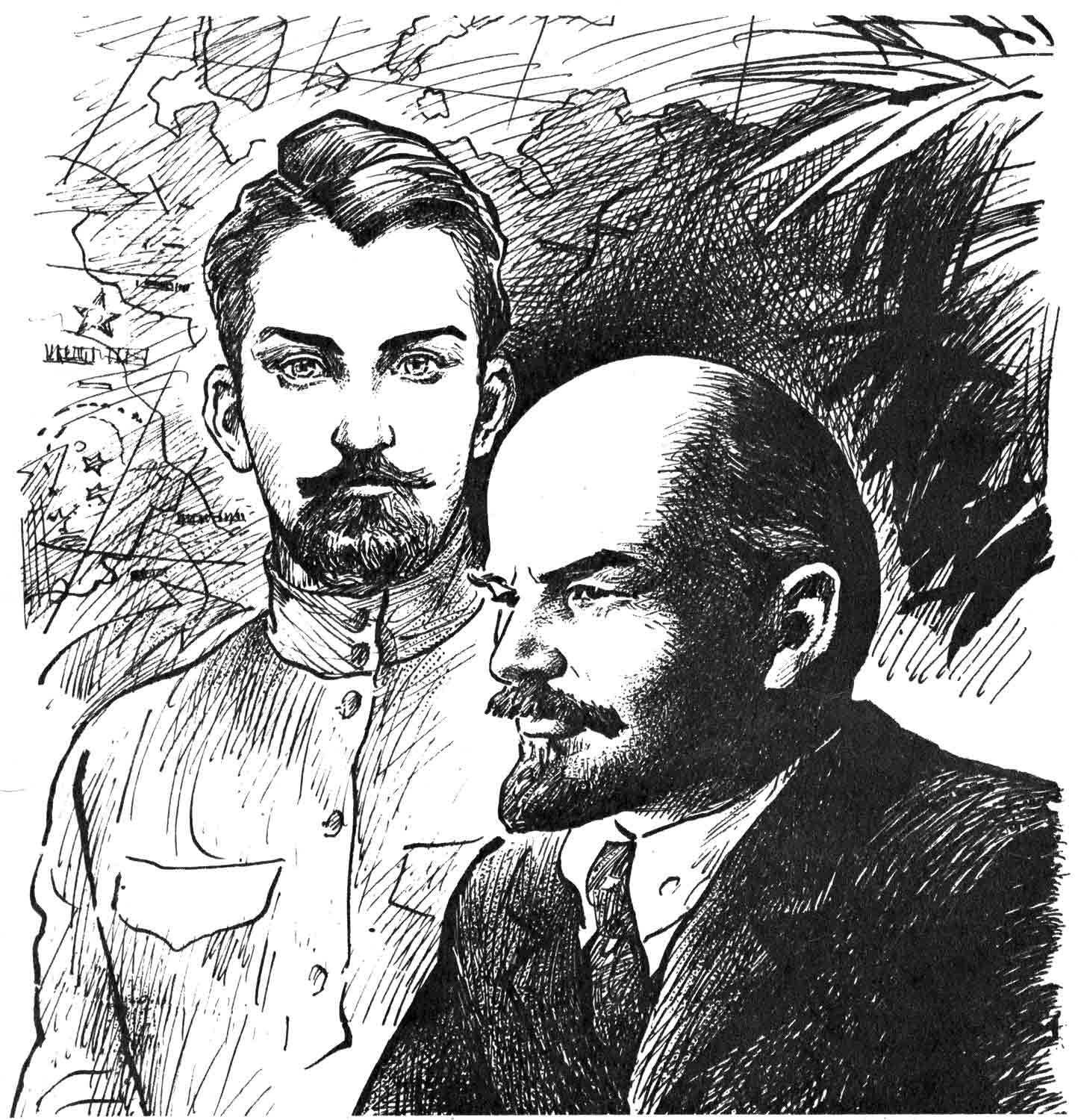

— ..I’m listening to you, comrades. Speak.

Noticing that one of the members of the delegation did not have enough space at the table, Lenin offered his chair, and he headed deeper into the office, to the window, where there were two leather-upholstered chairs. He took one of them and, carrying it almost across the entire office, repeated:

— Tell me. I'm listening to.

Placing a chair next to the chair in which Shchors was sitting, Lenin sat down, looked around at everyone, and prepared to listen. His face was so close that Shchors involuntarily had a flash of doubt: was all this real?

As if having guessed his thoughts, Lenin laid his head with his cheek on his palm, causing his entire body to bend over. Now their shoulders were almost touching, and Shchors clearly saw on Lenin’s face not only wrinkles, but also small, small reddish dots, similar to traces of freckles.

And there are many, many more features that no portrait, not even the best photograph, can convey.

Shchors wanted to remember all this firmly. Everything down to the smallest detail: the red temple next to the somewhat complicated pattern of the auricle, the corner of the eye under the sparse tip of the eyebrow, the eyelid in a network of dark veins, the outline of the nose, lips, chin, and the entire profile that is now unexpectedly and stunningly close, but has suddenly become unfamiliar.

Oh, how much even the best portraits don’t tell people!..

But then Shchors’s gaze met Lenin’s gaze, warm light splashed from the crack between the eyelids, and all the details of Lenin’s lively, slightly tense face immediately dissolved in this soft, slightly wary light.

The light in his gaze seemed to pulsate slightly from alertness. Shchors - he was a doctor, after all - knew that it was the muscle that fed the eye that was working, but the sensation was completely different: it seemed to him that it was a pulsation of thought. Living, insightful and tireless Leninist thought, which, like that working muscle, is also a source of energy.

Only incomparably more powerful.

Immeasurably powerful.

Immeasurable? Yes, sure.

It is difficult to grasp the scale of the power of Lenin's genius... Revolutionary power...

The scale of Lenin's thought is indomitable. She raised Russia. Like a lever.

Yes. Archimedes' lever. That is, this unquenchable ray, for which the fulcrum, found and strictly, weightily defined, is love for people...

All this will flash through Shchors’ thoughts later. One or two days later, when he gets on the train and immediately, almost instantly, becomes a prisoner of memories and thoughts about his meeting with Lenin.

And now he sits spellbound in a chair, opposite the end edge of Ilyich’s desk and seems to hear breathing, feel the pulse, even this eye muscle of Lenin. Shchors knows that now he will not forget any of the features of Lenin’s profile, he will not forget the fatigue under his eyes, the impetuous movements of his fingers, which had just drummed on the armrest of the chair, and now touched his, Shchors, hand.

— Your word, Nikolai Alexandrovich!

The voice (damn, this was still missing!) somehow hoarse, forcing you to clear your throat lightly.

In attacks, overpowering shrapnel barks and machine-gun gulps, not a wheeze, but here on you...

And Shchors spoke about the most important thing: that it is urgent to unite the efforts of Russians and Ukrainians in the fight against the Germans, with the Rada that has sold out to them, with all the hetmans and other bastards there. Otherwise...

— Necessarily! “It’s necessary,” Vladimir Ilyich agreed, interrupting Shchors. — And it’s good that the Ukrainian delegation came to Moscow.

This gave Shchors determination. He spoke more smoothly, his hoarseness disappeared. Shchors spoke as if at a rally.

With undisguised joyful surprise, Lenin turned and raised his head and even leaned back slightly in his chair, knitting his eyebrows smilingly.

— ...The German occupation is not only a shame. This is blood, torture, great human grief. The people are eager for weapons.

And then Shchors remembered the Zapalchishins. And about the promise that then, when parting with the detachment, he made to the youngest partisan - Zakhar. This strong and tall rural guy was the seventh of the Zapalchishins family who went to fight for Soviet power.

Seventh.

But now the only one. Because the rest - the father and five brothers - had already died.

Shchors himself did not notice how he began to talk first about old Zapalchishin - Afanasy, then about his eldest sons and, finally, about Zakhara. But he saw how Vladimir Ilyich had changed. Leaning further back in the chair, he clasped his fingers on his knees and squeezed them tightly. And it seemed that it was precisely from this movement that all the muscles of his face trembled barely noticeably and immediately froze: it became stern, tense, pulling his eyebrows and the lower wrinkles of his forehead towards the bridge of his nose.

As he spoke, Shchors now saw two faces in front of him: the frowning, stern, concentrated face of Ilyich and the still very young, slightly snub-nosed, under a cap of wavy, unkempt hair of Zakhar Zapalchishin.

— And you say there’s only one mother left at home? “Lenin unclasped his fingers on his knees and, as if not knowing where to put his hands now, put his left hand in his pocket, and with his right again touched Shchors’ elbow.

— Nikolai Alexandrovich, and you... No, I understand, you had no time for that...

Lenin thought for a minute, without finishing the question he wanted to ask, then he asked:

— Do you know where the Zapalchishins live?

“I won’t name the village,” Shchors shrugged his shoulders embarrassedly, “but they are from the Novozybkovsky district.” That's for sure.

“Novozybkovsky,” Vladimir Ilyich repeated mechanically and thoughtfully, looking at one point, shook his head. His eyelids closed tightly, but the same pulsating rays shone in the narrow, narrow slits between them. They were now directed to the side. It seemed that both their light and all the penetrating energy of this gaze were persistently and furiously searching in the land of distant Novozybkovshchina for an unknown, god-forsaken village in which the Zapalchishins were born and lived.

When, turning, the rays touched Shchors’s gaze, he was burned by the pain that overwhelmed them.

“You say there’s only one mother left at home?”

The suffering in Ilyich’s gaze was, as it were, a continuation of this question and, apparently, a whole whirlwind of thoughts evoked by Shchors’ story.

But with an effort of will, Vladimir Ilyich overcame the pain, his eyes widened and brightened, but a tiny line of concern, as if a trace of the pain he had just endured, still remained in them.

So, at least, it seemed to Shchors.

Continuing to speak, he constantly felt this line, saw this trace. And maybe that’s why his words were even warmer, more emotional about the soldiers who went on brutal attacks, about the commanders who grew up from the same soldiers, and again about Zakhar Zapalchishin, who, a week after his voluntary arrival in the detachment, was captured in a night sortie enemy non-commissioned officer.

— Hero. Just a hero,” Vladimir Ilyich exclaimed.

His face cleared up, he stood up, went to the table, reached for a piece of paper, took a pen, wanted to write something, but suddenly he became sad again, frowned, put the pen aside, returned and sat down on the chair.

“It’s a pity,” he said quickly, but with feeling. - It's a pity. At least know her first and patronymic... She's an old woman... It's simply inconvenient to address her in any other way. And there is no address

Shchors silently and helplessly shrugged his shoulders.

“That’s it,” Vladimir Ilyich perked up after a few seconds of silence. - I have a request to ask you, Nikolai Alexandrovich. Are you saying that the people you sent home will return at the first call?

— They will return, Vladimir Ilyich.

— So I ask you: if Zakhar Zapalchishin returns, find out more precisely where he is from, what his mother’s name and patronymic are, and write to her. On behalf of the Revolutionary Military Council... On my behalf... - Vladimir Ilyich looked around at all the members of the delegation and asked:

— Right, comrades?

Everyone nodded warmly in the affirmative and responded in unison:

— Very correct.

But there remained in Ilyich’s gaze, as it seemed to Shchors, something still unspoken. And these were probably the words that Vladimir Ilyich said to Shchors when, having escorted the members of the delegation to the door, he held his hand in his:

— And one more thing, Nikolai Alexandrovich... About this brave young man... Zapalchishin...

Vladimir Ilyich made short pauses, and this betrayed his excitement.

— If it happens that this young man ends up in your squad again... take care of him...

Anatoly Zemlyansky

Drawing by V. Lukyants

“Soviet warrior” No. 6 1977

*** |