Kings of Metal - Soviet steelworkers

The speaker, Anatoli Makarov, is a shortish lean man, light and quick of movement, expressive in conversation and with an ironic cast of mind. The speaker, Anatoli Makarov, is a shortish lean man, light and quick of movement, expressive in conversation and with an ironic cast of mind.

"You want to know how we make steel? Each of us does it in his own way. Ask a violinist if he can explain to you in words how he obtains a pure sound. Of course, we have our technical regulations but then, the violinist also has his score. Using the same score, one violinist makes people shed tears while another makes them feel like plugging their ears. With us it's pretty much the same."

MAN CHOOSES HIS FATE

"You want to know how I became a metallurgist? It was kind of accidental. I grew up in a village. It was near here, in the Zaporozhye Region. My parents are collective farmers. Well, after seven years at school I was determined to go to a city, to Zaporozhye. Lord knows why. Boyish curiosity, I suppose. Father didn't want to let me go. Incidentally, he still tries to persuade me to come home. Besides, I was only 13: I had entered school when I was under six. And I was small for my age. However, I had my way.

"I came to the city alone and made up my own mind what technical school I wanted to go to. In the metallurgical school they wouldn't even talk to me: First grow up a bit, I was told. Then I tried the industrial school, where I faced another refusal. What could I do? I was dead set against going back home. It would have been a personal defeat. I knew for sure I couldn't get a job because of my age (According to Soviet labour legislation, people under 16 should not be employed People under 18 should not be placed on health-hazardous and arduous jobs).

"Then I boldly — in despair — marched straight to the director of the metallurgical school, showed him my seven certificates of good work and conduct for all my years at school. The director was sympathetic; waving his hand, he said I could enter the school.

"When I finished this technical school I was offered a job at the Zaporozhstal Plant as a mechanic and electrician of oxygen installations. Then suddenly, you see, I fell in love with open-hearth furnaces.

"I did four years' work with oxygen, gained a high qualification, made good wages, became a team-leader and still I felt I just couldn't live without the open-hearth furnace.

"Our mixer department was then conducting experiments. Young engineers from Moscow had arrived. Well, I made friends with them. They were clever lads. Come and enter our institute, they said. I took their advice and decided to enroll in the Steel Industry Engineers' Institute in Moscow.

"With the 'help of God', I passed my entrance exams and was admitted. There followed five years of a fabulous life: I went to all the Moscow theatres and museums. Money from my father? He didn't have it to send. He has been an Invalid, Second Group, since the war and received pension only. I lived on my allowance and the student council always found places where a student could earn some extra money.

In the Plant Party Committee

"My academic progress? Well, in general, it was all right, above average. Though not much above.

"For my practical work I was directed back home, to Zaporozhstal.

"After the third year there was a moment when I was about to switch to the Automation Department (I was tempted by a post-graduate course) but at the plant I was told: of course, it's up to you to decide, but we need people in our open-hearth section.

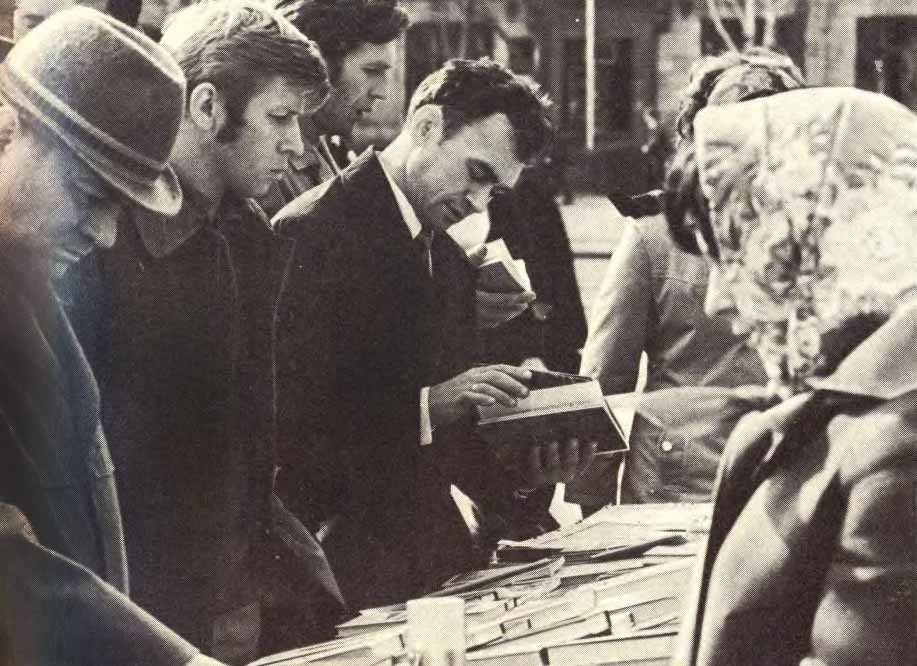

At the plant book kiosk.

"After that, everything was clear. I obtained my diploma and came back to the plant. I was offered a job at Furnace No. 1. For several months I was third assistant on the furnace: people wanted to size me up, see how 1 would behave with an engineer's diploma in my pocket. Then for an other two weeks I acted as second assistant and for two more as first, until 1 finally became head smelterman"

HIS PROFESSION

Smelting steel is a daily battle whose outcome hangs in the balance until the very last minute. The open-hearth furnace is always a conundrum, however many instruments you have on the control panel, however perfect the automatic devices.

Steel-making is a process that lasts several hours. However, no two minutes of it are identical. At times success depends on instantaneous decisions. If one makes a mistake, missing the moment the steel will be spoilt.

1 noticed the tone in which Makarov said "missing the moment". In a struggle like this, one just has to be a tiny bit superstitious. Only an automat has no doubts about success — but only because it does not care about failure either.

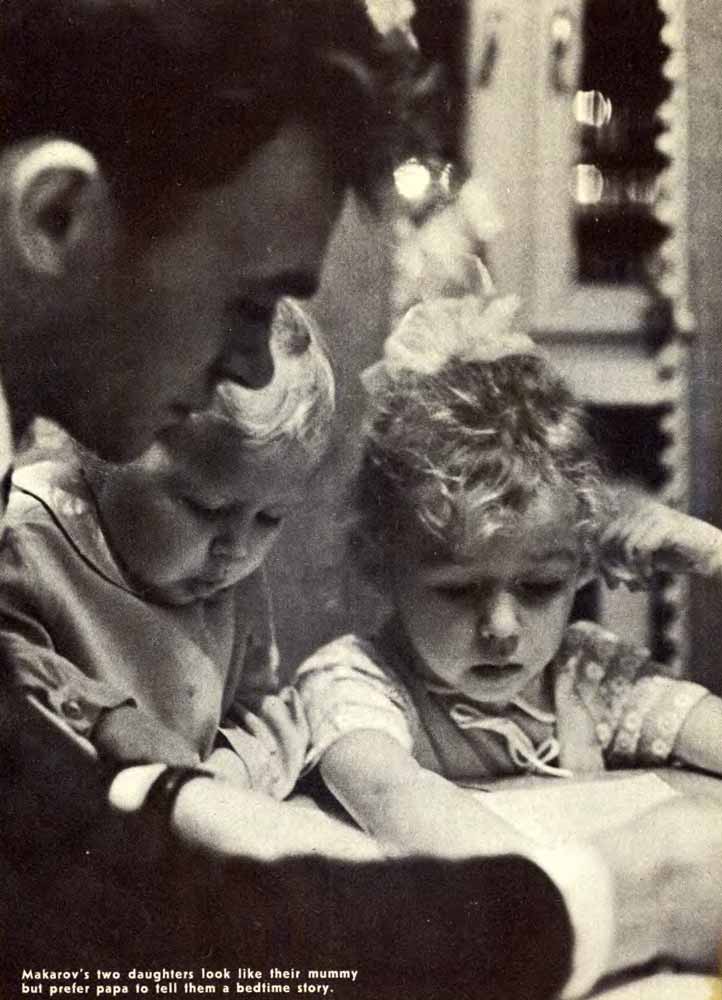

Makarov's two daughters look like their mummy but prefer papa to tell them a bedtime story

HIS COLLEAGUES

The turnace operates in four shifts. Each shift consists of the melter (teamleader) and five or six assistants.

Three smelter workers of Furnace No. 1 have secondary technical education, and Makarov has a higher education.

It is very hard to find time to study while working at the open-hearth furnace on a tour shift basis. And still, many do study; three assistants go to colleges and three more to technical schools. They will become full-fledged steelmakers.

How does it happen that a certificated engineer or technician starts on his career as a melter's assistant? Is melter’s job that of a worker or an engineer?

The author put this question to Makarov and to others he met at the plant, and here is a summarised answer.

Metallurgy is a field in which knowledge and skills fuse together and in which the engineer-worker distinctions are at times very relative and even barely perceptible.

It takes a specific talent and character: the ability to take risks and make quick decisions.

It also takes intuition and inspiration. After holidays the melter would prefer to work for several days as assistant melter — in order to regain his good form.

Besides, each furnace has its own "temper" — its own heat balance. And the skills developed by the steelmaker through handling one furnace may prove disadvantageous when he handles another.

"You can’t make steel by following one pattern," observed Misha Ryabchuk, the shop's Komsomol organiser and an engineer who until recently worked as foreman of the furnace section. "It is like removing an appendix. It seems as if the operation is very well known and thoroughly studied and still Lord knows what may happen."

Of course, the author has oversimplified many things and concentrated on the melter. There is also the furnace section foreman, supervising three furnaces, whose authority over the whole operation is very great, and there are assistants (some of them graduates or students of technical schools or even colleges). "Eighty percent of success," Makarov admitted, "depends on the assistants. If they make a mistake I can't save the situation."

And still, in this field of creation (surely work at the open-hearth furnace is a form of creation) the principal figure is the melter, with his boldness, his nerve, his inspiration, his talent.

"You ask me if I am going to become a foreman?" Makarov says. "Naturally. But not for a while. My self-respect won't allow it. I would hate people to say: 'He's a young foreman, so what can you expect of him?' Another year or so building up experience, then we'll see...

To the health of all our team members and to steelmakers everywhere!

by Edward ILYIN from the magazine MOLODOY KOMMUNIST

Photographs by Igor VINOGRADOV

Sputnik. №5 May 1974 |